Introduction to Evaluating Business Investments

Businesses often face the need to spend large amounts of money on assets that will be functional for many years. Here are a few examples:

- Equipment to improve an unsafe work situation or to protect the environment

- Equipment to test the consistency of products as required by the customer

- Equipment to package, label, and ship products according to the customer's specifications

- Equipment to reduce labor costs and improve the quality of products

- Purchase of a building instead of leasing space

Expenditures made for long-term assets are referred to as capital expenditures and are recorded as assets on the balance sheet. During the years that these assets (other than land) are used, their costs are systematically moved from the balance sheet to the income statement through Depreciation Expense.

New! We just released our 29-page Managerial & Cost Accounting Insights. This PDF document is designed to deepen your understanding of topics such as product costing, overhead cost allocations, estimating cost behavior, costs for decision making, and more. It is only available when you join AccountingCoach PRO.

Capital Budgeting

Limitations such as time, money, and logistics frequently prevent a company from moving forward with too many major expenditure projects at the same time. Instead, a company will often rank its projects by priority and profitability. By using a process called capital budgeting, the company decides which capital expenditure projects will be undertaken and when.

At the top of the list of capital expenditure projects are those for which no real choice exists (e.g., installing an updated sewer line within the plant to replace one that is leaking, correcting a safety hazard, correcting a code violation, etc). The remaining capital expenditures are usually ranked according to their profitability using a capital budgeting model.

Capital Budgeting Models

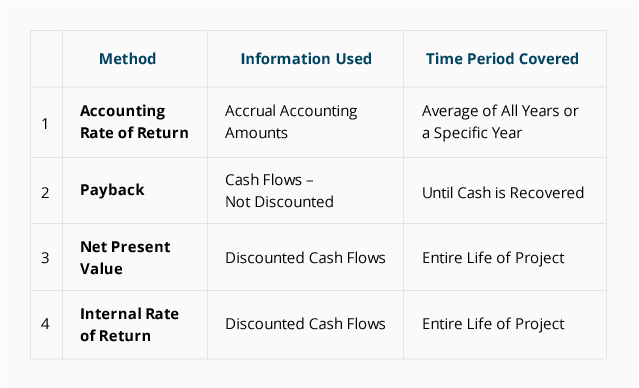

There are a number of capital budgeting models available that assess and rank capital expenditure proposals. Let's take a look at four of the most common models for evaluating business investments:

- Accounting rate of return

- Payback

- Net present value

- Internal rate of return

While each of these models has its benefits and drawbacks, sophisticated financial managers prefer the net present value and the internal rate of return methods. There are two reasons why these models are favored: (a) all of the cash flows over the entire length of the project are considered, and (b) the future cash flows are discounted to reflect the time value of money.

The following table highlights the differences among the four models:

Evaluating Capital Expenditures

Let's use the capital budgeting models to evaluate a potential business investment at Treeline Manufacturing, Inc.:

- Treeline Manufacturing must decide whether or not it should buy a new machine to replace its existing machine. Because the new machine is faster, it would eliminate the need for a worker now employed to run the existing machine during the evening shift. The initial annual savings are expected to be $24,000, with future cost savings expected to increase $1,000 or more per year.

- The old machine is fully depreciated and would be scrapped with no expected salvage value (no proceeds).

- The new machine costs $100,000 and is expected to have no salvage value at the end of its useful life of 8 years. For purposes of financial reporting, the machine would be depreciated over its 8-year life using the straight-line method. For income tax reporting, it would be depreciated over 7 years using the accelerated method. The company's income tax rate (federal and state combined) is 30%.

- The new machine would be placed into service on January 1 and a full year of depreciation expense would be recorded on the financial statements during the first year. For income tax purposes our analyses uses a half-year of depreciation during the first year.

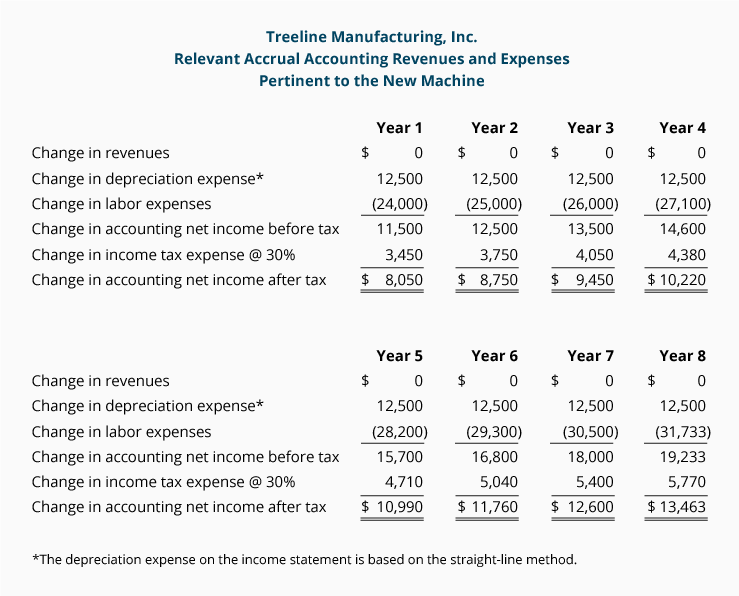

- The relevant accrual basis of accounting amounts have been identified as follows (the relevant cash flow amounts will be shown later):

Noncash, Nondiscounted Model

1. Accounting Rate of Return. This method of evaluating business investments considers the profitability of a project based on accrual accounting amounts found in the financial statements. The drawback of the accounting rate of return is that the net income amounts are not adjusted for the time value of money. In other words, $10,000 of net income in Year 4 is considered to be as valuable as $10,000 of net income in Year 1.

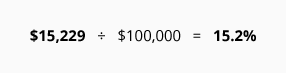

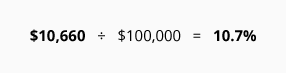

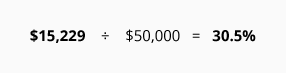

If the new machine is purchased, Treeline's income statements will show a reduction of labor expense of about $24,000 in Year 1 and $31,733 in Year 8—an average of $27,729 during the 8 years. The income statements will also show additional depreciation expense of about $12,500 per year (the $100,000 cost of the machine and a useful life of 8 years with no salvage value). The net result of the average annual labor savings of $27,729 minus the additional annual depreciation expense of $12,500 is an average of $15,229 of additional net income before income tax expense. Assuming a combined federal and state income tax rate of 30%, the net income after income tax expense will average approximately $10,660 per year.

Treeline's balance sheet will start with the new asset's carrying amount (or the book value) of $100,000. The book value will decrease to $0 at the end of 8 years. In other words, the balance sheet amount will average about $50,000 per year during the 8-year period.

At this point, Treeline must choose one of the following calculations to estimate the accounting rate of return. (As with most "return" calculations, the numerator comes from the income statement and the denominator comes from the balance sheet.)

-

Average additional accounting net income before income tax expense ÷ the additional original investment:

-

Average additional accounting net income after income tax expense ÷ the additional original investment:

-

Average additional accounting net income before income tax expense ÷ the additional average investment:

- Average additional accounting net income after income tax expense ÷ the additional average investment:

» Tin mới nhất:

- Những Website Check Lỗi Ngữ Pháp Tiếng Anh Chất Lượng (18/05/2024)

- The writing process and assessment (18/05/2024)

- Những kinh nghiệm làm đồ án dành cho sinh viên kiến trúc (18/05/2024)

- Vai trò của các công cụ khuyến mãi đối với hành vi tiêu dùng (18/05/2024)

- Quyết định đầu tư chứng khoán và các mô hình nghiên cứu (18/05/2024)

» Các tin khác:

- Các dấu hiệu nhận biết các khoản cho vay có vấn đề (18/08/2017)

- RỦI RO CHO VAY (18/08/2017)

- Three main type of Marketing Research (18/08/2017)

- What is management accounting? (18/08/2017)

- Capital budgeting applications (18/08/2017)

- Đổi mới đào tạo sư phạm phải theo đúng quy luật cung cầu (18/08/2017)

- Đổi mới đào tạo sư phạm phải theo đúng quy luật cung cầu (18/08/2017)

- Muốn đầu tư nhưng không hiểu bitcoin là gì? Hãy đọc lời giải thích chỉ tốn của bạn ít phút sau đây (18/08/2017)

- Làm giàu kiểu Jeff Bezos (18/08/2017)

- Các phương pháp định giá cổ phiếu (Phần 2) (18/08/2017)